Valuing Vulnerability in Language Teaching

A couple of years ago, I received an email from a former student of mine, who had joined the programme as a beginner user of the language, was about to graduate and had just been selected for a job abroad.

That message made me think about my students’ transition to university and what this entails in my subject. In the learning of languages, it is a transition that involves a lot of damage-repair around a generalised perception that second language acquisition is associated either with talent, social class and privileged backgrounds, or a set of cliched ideas of cultural diversity.

When I ask my undergraduate students about their motivations to choose a credit-bearing language beginner course, they often mention that learning a language other than English may be useful when traveling - in a very practical and utilitarian way - or valuable when they want to know more about other cultures. There are really good intentions behind these reasons. But they are not always realistic for those taking a language beginner or post-beginner course (which are often the options available to students who stopped engaging with languages a long time ago).

Students are not to blame for this, as this is what they’ve often been told is the purpose of learning a new language. It is even part of the course marketing strategy too: you just need to replace holidaying with employability! But unless you’ve already been studying a language for a while, achieving that accurate and effective level of intercultural communication is a skill that requires more than a hundred hours of classroom interaction. So, what is, then, the main goal of such courses?

Even if it’s not the advertised intended learning outcome of the course, nor the most appealing skill to develop to the average goal-oriented 18-year-old student mind, empathy is the core of the module. Empathy is also what underpins and enables many of the values and graduate characteristics that the university is promoting in its newly reviewed Education Strategy for 2019-2025 - which, among other things, aims to support students in becoming “proactive, inclusive, resilient and creative agents of change [prepared] for life beyond graduation.”[1]

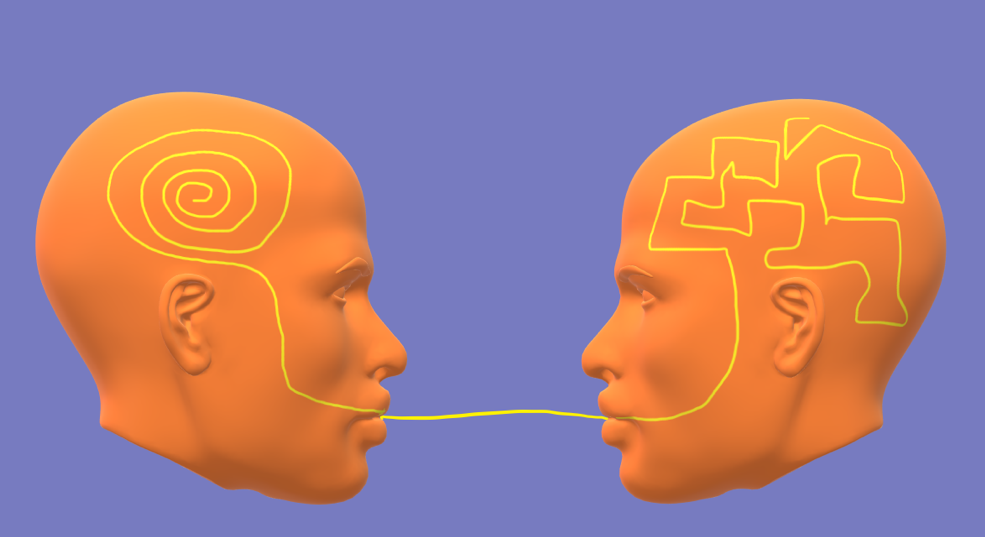

As a teacher of language, a lot of my work is about accompanying students in a journey through human vulnerability.

In a way, learning a language from scratch as an adult helps you realise how disempowering it can be to see yourself (and others) lacking a set of very basic communicative skills. All of a sudden, even if it is just for a few hours a week, you become less able than you usually are. This often brings out the significance of exercising and sharing empathy towards those who, for whatever reason, may find themselves constrained or prevented from engaging as much as they would like to in a certain activity.

I must admit that, although it’s usually fun, learning a new language also comes with some embarrassing moments and very humbling mistakes! For example, when you try ordering a coffee but you end up asking very submissively for permission to drink. Or when you find out in horror that you’ve actually asserted that you’re really hot and sexy rather than just “good, very good, thank you”. Other times, you have to embark into a non-always-pleasant road of self-discovery in order to progress and dare to produce awkward sounds in your mouth and learn to accept and appreciate these new and often uncomfortable and imperfect pronunciations as a voice of your own. At the end of the day, my students find themselves needing to be brave enough to embrace their vulnerable selves, and being prepared to feel as lost as a “foreigner” or a newcomer, who does not always know what to say or how to say it, or whether it is even appropriate to say anything in a given context.

you find out in horror that you’ve actually asserted that you’re really hot and sexy rather than just “good, very good, thank you”.

As a teacher of language, sometimes it is complicated to defend the utility of exploring imperfection and vulnerability - especially within a mainstream educational discourse of excellence and success. I often find myself swimming against the tide, leading courses where I know students will soon not feel like high achievers. In my seminars, I know we will experience unease and limitations, as students will rarely be able to express themselves in the same way they would if they were using a language in which they are fluent. Instead, we will have to come to terms with some sort of beta version of their sophisticated thoughts. At times, I wonder if this is, in fact, a “marketable” learning experience. I wonder if students can really see the point of it all.

What I have grown to realise is that a substantial part of my work is about accompanying students in a journey through human vulnerability. I hope that this experience helps make them, if not linguistically fluent, more resilient and potentially more inclusive human beings. A non-specialist undergraduate language course in itself is not going to produce accurate translators or interpreters. But it can help our future graduates in Biosciences, Business, Politics or Humanities to become professionals who are not only experts in their fields, but are also able to understand and support others when they are struggling or facing difficult circumstances.

[1] https://www.exeter.ac.uk/about/vision/educationstrategy/